Hi-tech Dutch ID cards helped Nazis identify, exterminate Jews: What does that teach us about the ethics of technology & the choices we are making today?

I can, in part, blame my fascination for The Holocaust on reading too much of Leon Uris in my teen years. This fascination intensified on the trip to Berlin in 2014 and continues to be a theme of my explorations in Europe since. So this past weekend, on a loose limb on a Saturday morning, I decided to explore the Jewish Quarter in Amsterdam. The motivation was a listing for an exhibition titled Identity Cards and Forgeries: Jacob Lentz and Alice Cohn on the IAmsterdam page. On a recent trip to China, a PhD researcher had presented at a workshop we co-organized her preliminary research on documents and identity that mentioned the use of ID card forgeries to help migrants access services. That discussion played in my head, as much as the recent heated debate in India on privacy and misuse of information collected under the UIDAI project, popularly called the Aadhaar, which the Indian government is aggressively developing in the form of a universal identification system for the country. The Supreme Court of India is currently in the midst of hearing petitions that contend that the Aadhaar identification programme violates an individual's fundamental right to privacy. A curious me arrived at the National Holocaust Museum and the exhibition did not disappoint!

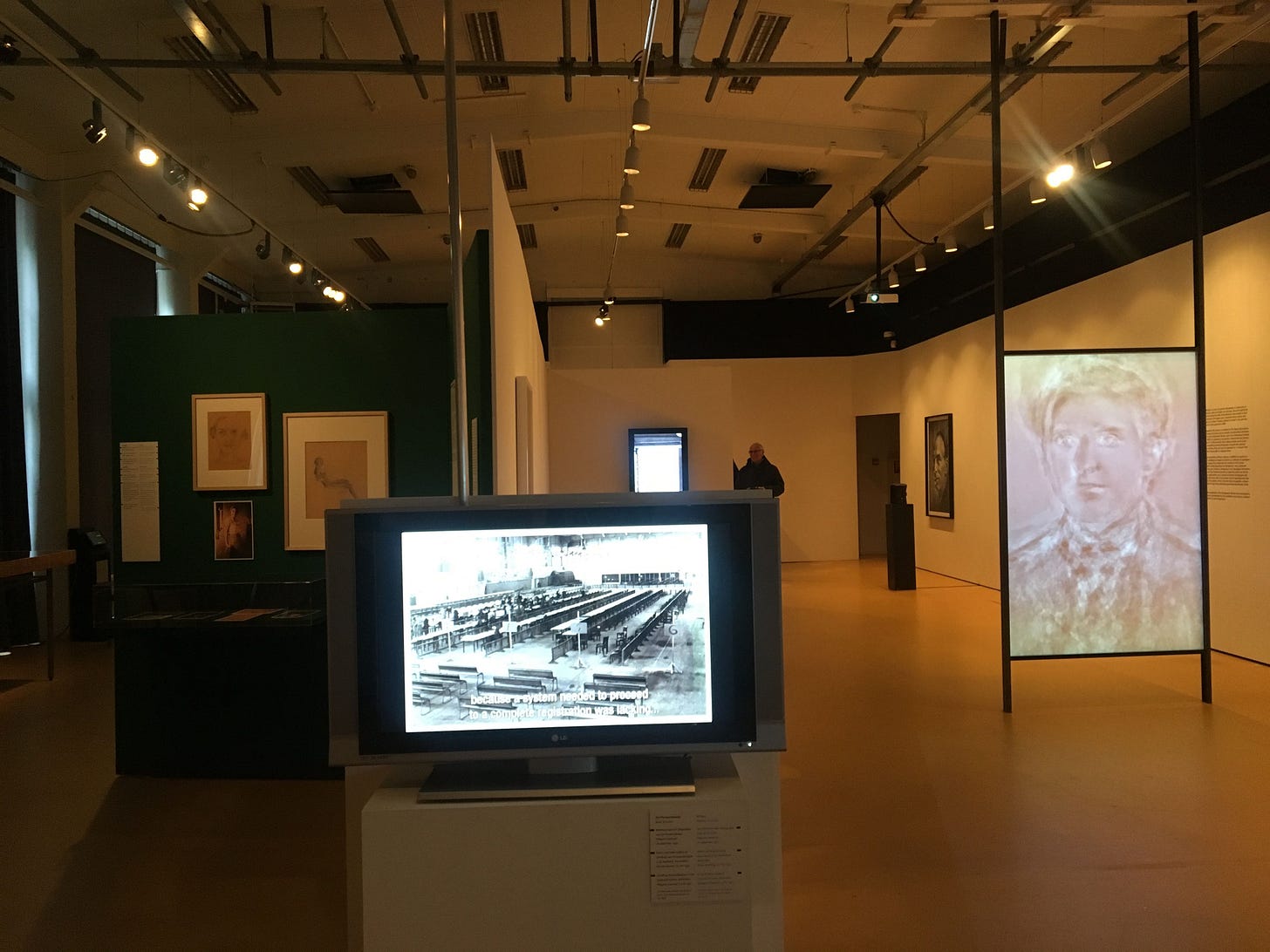

Set in an oppositional format, the left half of the exhibition space showcased the work of Jacob Lentz who, as the head of the Dutch National Inspectorate of Population Registers, had been at the forefront of designing a highly secure and for the time hi-tech system of ID cards from 1936 onward. While Lentz and some of his colleagues seemed to have designed the system expecting every Dutch citizen carry an ID card, interestingly in March 1940, the Dutch government decided not to implement this system. Their reason? That it was contrary to Dutch tradition.

But of course the highly sophisticated, and virtually non-forgeable, ID card system was ready for the Nazi occupiers to use when the Netherlands fell to German forces post the bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940. The ID card system was brutally used by the Nazis to identify Jews (with a large J on the card itself), in order to initially curtail their civic rights and eventually deport them to concentration camps where they were largely exterminated in gas chambers. Lentz, as one of many bureaucrats who inadvertently aided the Nazi genocide, is cited as an example of Hannah Arendt's famous Banality of Evil hypothesis, which highlights the absolute ordinariness of the human beings who perpetrate acts of evil merely by being complicit. Read in another way, one may say that the compliance of ordinary people under conditions of terror are sufficient to aid evil. Something we in India could keep in mind if we were ever to be on the scene of a horrendous rape, lynching or honour killing, all of which are alas becoming all too common!! I won't go into the larger implications of the 'banality of evil' in the Indian context as manifested by, for example, widespread self-censorship in public life and social media in the face of a vindictive regime served by an army of online trolls. I have written on those issues before.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men should do nothing.”

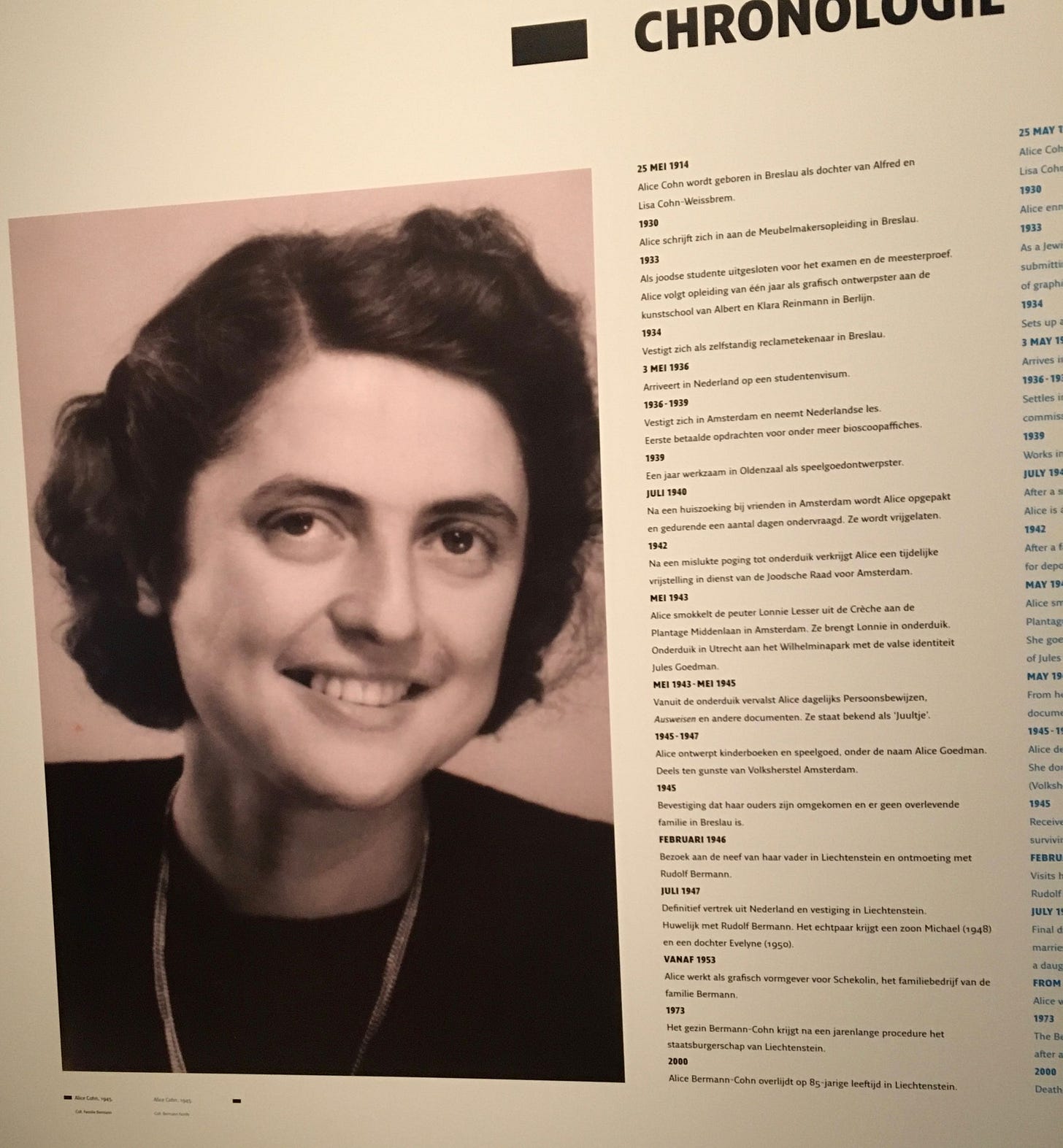

~Edmund Burke On the opposite side of the exhibit, was displayed the work of Alice Cohn, a German-Jewish graphic artist and member of the Dutch resistance who obsessively and often successfully forged these ID cards to help innocents escape. The work of the Resistance is marked by the very opposite of what I have discussed above, the involvement of ordinary people, often from the non-persecuted majority, in a commendable demonstration of altruism usually at considerable risk to themselves (on that note, check out this fantastic NatGeo piece on the psychology of altruism). Those stories reinforce our faith in humankind and at the end of the exhibition, I was left with a positive feeling despite the overwhelmingly "heavy" sense one has in a building that is dedicated to the memory of those persecuted and murdered during the Holocaust.

Exhibition space

The ID cards for Jews, marked with the prominent J

Alice Cohn

Some of Alice Cohn's graphics work

Alice Cohn's story has a specific resonance with the history of the building that houses the Museum. One of her bravest acts was the use of a forged identity for herself to be able to walk into a creche, located next door to the Museum, and rescue the child of a Jewish couple who were her friends. The creche is where the children were kept before deportation, while the parents were crowded into the Hollandse Schouwberg, a theatre building on the other side of the street. The story is that Director of the non-Jewish School that was run in the Museum building, and the woman who ran the creche collaborated to smuggle out over 600 Jewish children to safety, out of the clutches of the Nazis and into foster homes where they grew up safe and sound. I held on to these stories of altruism even as I wept at the small but evocative collection of material artefacts from families who died in the Holocaust.

Where the Amsterdam Jews were held before deportation

A bit further down the road, the Portuguese Synagogue. The Jewish population in Amsterdam immigrated from Spain and Portugal (the Shephardic Jews.) during the Reformation.

[gallery ids="15857,15859" type="rectangular"]

The Dutch Jews were concentrated in Amsterdam, and so this community was hit hardest by the Holocaust. About 107,000 Dutch Jews were killed in the concentration camps, some 5,200 survived while the Dutch Underground was successful in hiding 25-30,000 Jews and hence saving their lives. Among them were these 600-odd children who were aided by the school. Franz, the volunteer who narrated us the story, told us that though a few of the parents of these children did return from the concentration camps, they were "neither right in the body, nor in the head" and the reunions were almost as difficult as the separation. The impacts of extreme hatred and mass ethnic cleansing are often discussed in terms of death and annihilation. Sadly, in our world today, these words have become normalized. It would do us all well to remember that between living and dying are myriad states of pain and half-baked existence, the personal and social consequences of which are almost as unbearable.

The pall of the Holocaust hangs over Europe decades after. As the extreme conservatives rise over the continent and indeed the world, people worry and fret but alas, also forget. And evil has the chance to be banal again.