Including the 'little people': The crowd as audience and muse

There is so much fabulous art, but can we make it accessible?

Art makes itself felt with a punch in the gut, a lurch in the heart, a tear in the eye. Sculptor K S Radhakrishnan’s 'Crowd’ elicited a gasp and a stopping in my tracks till the eye could take it all in, and the mind could grasp the incredible fluidity and dynamism in front of me. The Crowd invites you, then pulls you in. You find yourself weaving in and out between these supple human figures, taking in their grace, energy and gamut of expressions. Slowly, your fingers caress their faces, and your eyes flutter close. The dappled winter sunshine warms your face as you give yourself up to your feelings. Later, reading about Musui, Radhakrishnan’s Santhal muse and his female embodiment Maiya, you think about how a particular human form inspired and then transformed into a million different moods, emotions and messages.

A retrospective of this amazing artist’s work, curated by art historian R Siva Kumar, was recently exhibited at New Delhi’s Bikaner House, a wonderfully restored historic building at India Gate, right in the heart of Lutyen’s Delhi. A combination of popular restaurants, crafts stores, and art galleries gives the venue a natural footfall, and it's heartening to see it grow in popularity. Its certainly a favourite place for our family to hang out!

Proceeding through Radhakrishnan’s retrospective, I was struck by his mastery of his medium and the sensitivity of the themes he explored. He ‘saw’ the ordinary people around him and captured their everyday struggles in a bustling, hostile city. In narrating the lived realities of these “little people”, their ups and downs, disappointments and celebrations, he draws attention to the process of making new lives in new places. Using the imagery of a boat, he illustrates the liminality of migrant lives, neither here nor there, but always aspiring and trying, always striving for more. The importance of “little people” has also been a constant theme in my work. I write about how poor migrants resist and negotiate footholds in hostile urban environments and how women bargain within patriarchal social structures to gain unusual freedoms and dream of the impossible.

And yet, ironically, there were no little people at Bikaner House to experience the incredible beauty of Radhakrishnan’s art. The heart of colonial Delhi exudes power and privilege. Though the city’s crowds were comfortably sprawled and strolling across the open spaces around India Gate, venues like Bikaner House remain hidden and daunting.

In contrast, a visit to Red Fort, where the first Art, Architecture and Design Biennale (IAADB 2023) organised by the Ministry of Culture, offered a glimpse into how locating art and design in public and accessible spaces can transform the manner of their consumption. The Red Fort is one of Delhi’s most popular tourist sites. It saw over 1.3 million visitors in 2022. Located in Shahjanahanad in Delhi’s densely populated historic core and well connected to the Metro rail system, it attracts families and students from the city and elsewhere.

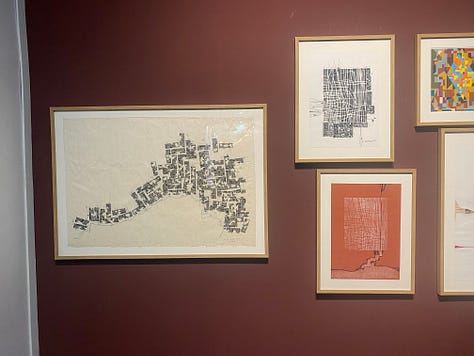

Hosting the IAADB on the Red Fort’s premises was a smart decision. The barracks, constructed over 100 years ago by the colonial British army and renovated into exhibition spaces in 2019, offered a wonderful setting for curated exhibitions on folk and indigenous art, temple design, gardens, post-Independence architecture, and women in Indian architecture. The last two were particularly interesting to me, given my background in architecture. But more than the quality and visual impact of the exhibits, I was heartened to see the large numbers of people walking through these spaces. Little children were peering intently at architectural models, teenagers were taking selfies against large, intricately designed light fixtures, families were discussing what they liked and didn’t, and lovers were dreamily wandering the galleries while holding hands.

Outside, in the spaces between the barracks, two burkha-clad women clicked pictures of their children posing before a sculpture. A group of teens shared food on the lawns. A girl was snoozing, sprawled against a tree, enjoying the winter sunshine. I thought this visual might make a good cover for a reprinting of Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan, and Shilpa Ranade’s famous feminist take on urban spaces - ‘Why Loiter?’.

Watching people enjoy the incredible art, architecture and heritage around them in a relaxed and natural manner was the most enjoyable part of the Biennale. Of course, so much more can be done to bridge the gaps between the crowd and art, but what we saw was a testimony to how well-located and accessible art can transform public spaces and open new worlds to those who are otherwise shuttered off from this wonderfully creative world. The little people must certainly be the Muse but first and foremost, they must be the audience.

Hey Mukta, I love the way you put this: “the liminality of migrant lives, neither here nor there.” Isn’t that the truth?

I research migration so I think a lot about it. But liminality and in-between-ness interests me in general as well. Binaries are overstated!