Unpacking Kashmere Gate's market areas

More tough questions about conservation and redevelopment

Many thanks to the wonderful Masters in Social Design students of Ambedkar University Delhi and my dear friend Venu, who teaches them, for this opportunity to learn more about the fascinating complexities of Kashmere Gate.

Puraani Dilli (old Delhi) is a vibe! Well, that’s just a funky way of conveying the feeling of being transported into a confusing world where the hustle and bustle of wholesale trade occurs in medieval and 19th-century structures of varying historical and cultural significance. In last week’s newsletter, I mulled the idea of what informs land use choices in cities where land is a highly coveted commodity - is it profit, the idea of cultural value, or a moral choice of protecting the vulnerable (whether people, the natural environment or the built environment)?

Following that thread, this week, I bring glimpses from a curated walk conducted by students of Ambedkar University Delhi for a few of us who were examining their semester-long project of understanding the ongoing processes in the wholesale automotive spare parts markets in the Kashmere Gate area of Delhi. Here, we experienced the humdrum architecture of commerce, which, though located within a designated heritage area, does not seem to have much intrinsic heritage value. Urgent commercial logic drives redevelopment in these spaces, but the heritage tag prevents a fully market-oriented redesign, thus disincentivising building owners from improving the quality of buildings and services. Hearing the students’ narratives about this rapidly reconfiguring neighbourhood, I thought about the inevitability of change and who wins and loses in the eternal negotiations between market forces and regulatory frameworks.

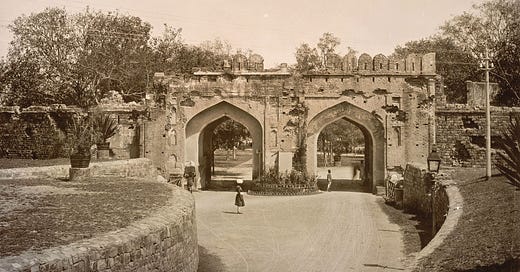

Kashmere Gate is historically significant as the northern gate of the walled city, one of fourteen, built by Mughal Emperor Shahjahan in the 1630s. Recreational gardens and country homes first populated the area outside, and in the early 19th century, British merchants built residential estates here. Kashmere Gate was a significant battle site during the 1857 First War of Independence, referred to by British historians as the Mutiny. Post-1857, the British set up civil lines further north, and the neighbourhood around Kashmere Gate became an entertainment and commercial area, retaining this status till New Delhi was built in the 1930s.

We saw vestiges of these histories during our walk. Many old structures look run down, and some already have caved roofs, but most buildings continue to be in use despite the decline. The plinth of a late Mughal mosque now houses retail shops, and the entrance to the masjid and madrasa (religious school) is in an obscure corner. The hotels that once dotted the area have become warehouses, and the ground-floor retail stores now house wholesale businesses.

From a heritage conservation perspective, this transformation from entertainment and retail to warehousing is by no means benign. Storage space is maximised by boarding up windows, hence altering facades. New buildings slowly cover open areas, with more shops and warehouse space.

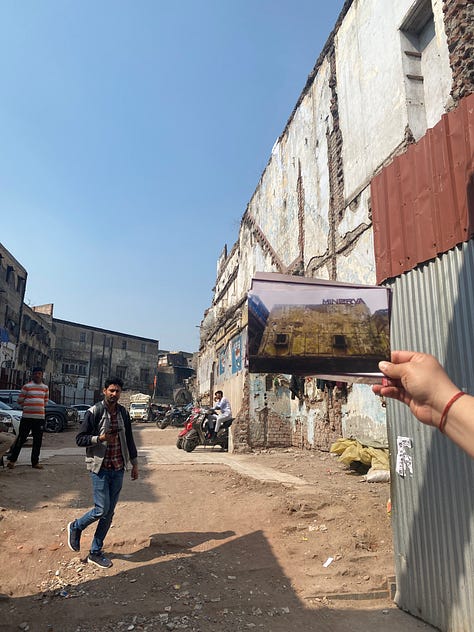

We found ourselves standing on the marble floors of a recently demolished cinema hall, the erstwhile ‘Minerva’, staring perplexed at Pepsi ads painted on a wall. What would replace this local landmark? More warehouses? Considering that business was declining, this seemed counter-intuitive, yet, given the stringent heritage zone restrictions, what sort of new development was possible in such a prominent location?

We were given to understand that heritage laws require permits for modifications and redevelopment. Additionally, many shop users pay low rent because of outdated rent ceiling laws. Hence, building owners cannot realise profits from redevelopment, nor are they interested in the upkeep of these structures. However, we also learnt that the complex red tape around getting building permits in such a heritage zone is regularly overcome by bribing officials. Hence, alterations and constructions that contribute to sustaining businesses continue to take place.

Not even the open spaces are spared these transitions. The courtyards of the market are filled with handcarts, storage boxes and parked vehicles. These spaces double up as sleeping and leisure spaces for the head-loaders who work in the market. Shanties built of makeshift material dot the building roofs. The students’ work explored the idea of home inside a commercial space, investigating infrastructures and processes of survival. How do people cook, eat, sleep? Where do they store their belongings? What makes them feel safe? We saw workers’ bodies everywhere as they carried boxes, pulled carts, slept, chatted, waited and cooked. I wondered how their ubiquitousness in such spaces contrasts sharply with their total invisibility in business regulations or conservation policy.

Looking at the dilapidated state of these neighbourhoods and the disincentives for commercial redevelopment, it is difficult to imagine a credible future for these areas and the people who live and work in them. It is painful to think that this layered urban fabric with such a rich history will soon decay and cease to exist. Can we devise an adaptive approach that aims for a neighbourhood that allows a peek into the past while accepting change and making way for the future? One that allows for a collective and comprehensive development vision? Now that is a million rupee question!